N.B. The DSM currently being constructed is referred to in this article both as DSM-V and DSM-5. The APA at first used the appellation DSM-V, but later on began calling the document DSM-5.

Rarely has the medical world—and the general public, for that matter—been witness to an open drama such has taken place over the past two years in response to a medical association’s announcement that it was going to revise its diagnostic categories. A war broke out with unlikely sides: Two former editors of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) on the one side and, on the other, the officers of the APA and the leaders of the APA’s current Task Force that is revising the DSM. Because of the Internet, the battle has been very public, and the APA has found itself on the defensive as it became repeatedly bombarded by open letters and columns in various media outlets. These missives were immediately seized on by multiple bloggers. The hallmark of the campaign by the former editors has been marked by unrelenting, inescapable repetition, which has added strength to their broadsides.

The scenario started simply and privately in April 2007, five years before the revised manual was scheduled for publication. Robert Spitzer, the psychiatrist who had headed the APA’s Task Force that revised the association’s third diagnostic manual in 1980 (DSM-III), dropped a two-line request to a colleague, Darrel Regier, Vice Chair of the Task Force that is currently updating the Association’s fifth manual (DSM-5). Would it be possible for Regier to forward to him a copy of the minutes of the Task Force’s first two meetings?

Regier answered Spitzer quickly, saying summary minutes would be available to individuals like him for private use, but asking him to wait until the APA Board of Trustees formally approved the membership of the Task Force. After an interval, having received no minutes, Spitzer renewed his request. But nine months passed before Regier gave Spitzer a definitive answer in February 2008: Due to “unprecedented” circumstances, including “confidentiality in the development process,” David Kupfer, Chair of the Task Force, and Regier had decided the minutes would be available only to the Board of Trustees and the Task Force itself. However, said Regier, the APA membership would be kept aware of DSM developments at professional meetings and through reports in various psychiatric publications. But an article four months later in the Psychiatric News, the APA’s official news magazine, propelled Spitzer into public action. We are now at June 2008, fourteen months after Spitzer’s original request.

In a letter to the editor, June 11, 2008, Spitzer began: “The June 6th issue of Psychiatric News brought the good news that the DSM-V process will be ‘complex but open.’” And, he added, just a few weeks before, the outgoing president of the APA had stated that in the development of DSM-V the APA is committed to “transparency.” Then Spitzer expostulated: “I found out how transparent and open the DSM-V process was when [Regier] informed me that he would not send me a copy of the minutes of DSM-V task force meetings . . . because the Board of Trustees believed it was important to ‘maintain DSM-V confidentially.’” Spitzer then made available in his letter a paragraph from the Acceptance Form that all Task Force and Work Group members had signed stating that during their term of appointment and after, they would not “make accessible to anyone or use in any way any Confidential Information.” “Confidential Information” was defined in broad legal terms.

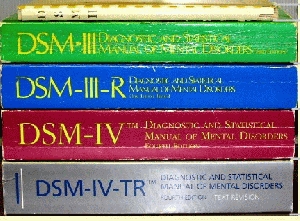

Spitzer continued: “I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. Laugh – because there is no way Task [F]orce and Work Group members can be made to refrain from discussing the developing DSM-V with their colleagues. Cry – because” to revise a diagnostic manual in secrecy destroys the scientific process, “the very exchange of information that is prohibited by the confidentiality agreement.” Spitzer asserted that the making of DSM-III, III-R, and IV, by contrast, had been open processes where the widest exchange of information with all colleagues was encouraged. Spitzer did not stop with this letter. Once galvanized into action, he began an unrelenting campaign against the “secrecy” of the fifth DSM revision process and urging “transparency,” soon forcing the APA to defend itself. (Eventually, as I will discuss below, Spitzer was joined by Allen Frances, the editor of DSM-IV and its revision, DSM-IV-TR. They were able to mount a highly visible battle by publishing their manifestos in a psychiatric news magazine independent of the APA, the Psychiatric Times. Frances came to urge action on a wide variety of issues, publishing continual and frequent warnings of dire results if the APA leadership continued on the path it had chosen. The latest as of this writing is centered around a critique of the “impossible complexity” of the new DSM-5 section on Personality Disorders.)

But before Frances joined the fray, Spitzer hammered on certain themes and charges tirelessly in a variety of publications spread over many months. The repetition itself, rather than appearing redundant, added intensity to his challenges, which can be summarized as follows: (1) The DSM was being developed in secret because the Task Force and Working Group (specialty committees) members had had to sign confidentiality agreements. (2) Revising a diagnostic manual behind closed doors defeats the very scientific process that is supposed to ensure the best possible scientific outcome. (3) His repeated attempts, he charged, to get the DSM-V and APA leadership to explain their departure from the past policies that had been employed by the editors of DSM-III and IV, had brought forth answers that made little sense. The leadership, Spitzer would often state, maintained that the working groups and Task Force needed privacy to freely discuss and candidly exchange views with others without worry that tentative views might be made public. But, he asserted, it is unprecedented that distinguished researchers and clinicians would be reluctant to speak candidly, something they did openly all the time. The APA had also argued that making minutes of meetings and conference calls would jeopardize the APA’s intellectual property rights, but it had not explained how this would happen. Finally, (4), the APA should return to the policy that the participants in the DSM process be encouraged to interact freely with their colleagues and that summaries of DSM-V meetings and conference calls be made available to interested parties. In addition to Spitzer’s concerns, other commentators began to question whether the participants in the DSM-V process had conflicts of interest because of ties to the pharmaceutical industry.

In vain did the APA and its supporters repeatedly–in public presentations, in postings online, and in written articles and letters–recount information about the history of the DSM-V revision process. They pointed out that work had been going on since 1999, which in itself, they argued, showed the process was “open and inclusive.” As evidence they cited the publication of two volumes of white papers that, starting in 2002, discussed in detail the many psychiatric issues that would have to be addressed. The APA also reported that it had publicly worked in conjunction with the World Health Organization (WHO) and the World Psychiatric Association to develop an NIMH conference grant application to review the research base for mental disorder diagnoses. Several governmental organizations dealing with public health had subsequently joined this effort, and the five-year grant supported thirteen international conferences, which had produced over 100 scientific articles. Many 100s of scientists and clinicians, it was emphasized, had been involved in these activities. Such factual data from the APA, however, did little to stem the vigor of the attacks by Spitzer, and other critics became attracted.

Spitzer kept repeating his calls for “full transparency” and the posting of the minutes of all meetings and conference calls. “Anything less,” he stated, “is an invitation to critics of psychiatric diagnosis to raise questions about the scientific credibility of DSM-V.” [Spitzer post of Nov. 26, 2008] By early 2009, Spitzer’s campaign began to bring results, and the APA said it would post Task Force and Work Group reports (though not minutes) on the DSM-V web site, and it explained its vetting procedures to weed out those psychiatrists with excessive ties to pharmaceutical companies. Also, spelling out what they had done already, the APA pointed out that the American Journal of Psychiatry had been steadily publishing editorials on a variety of DSM-V diagnostic issues. The APA president again declared that the DSM-V process was more open than any previous process and that APA members as well as the public would have the opportunity to comment on the web site. And in the Wall Street Journal Health Blog, under the heading “Psychiatrists Bash Back,” David Kupfer, the Chair of the DSM-V Task Force, was quoted as saying he wanted to set the record straight because “some of us have gotten . . . sick enough about playing defensive ball and being taken out of context.” The confidentiality clause, he explained, was not keeping the revision process secret but rather protecting, as the WSJ blogger wrote, “the intellectual property of the DSM . . . . The intention was to prevent someone involved in the process from, say, writing a book about his or her experience about the revision process prior to the DSM-V’s publication.”

This did not silence Spitzer. He wrote again in the Psychiatric Times, repeating his usual arguments and now comparing the DSM-V process unfavorably to those of DSM-III and IV, accusing the DSM-V leadership of certain “restrictions on the appointment of advisors and consultants.” By contrast, he declared, during the making of DSM-III and IV, in order “to get the widest possible opportunity for input, essentially anyone interested in becoming an advisor was appointed.” Finally, he registered astonishment that Darrel Regier had stated that “DSM-V will be more etiologically based than DSM-IV,” proclaiming, “there is insufficient evidence to justify making the DSM more etiologically based.” (One of the crucial—and ultimately revolutionary– objectives of Spitzer’s DSM-III had been to make DSM diagnoses purely descriptive on the grounds that in psychiatry little is known about the etiology of mental disorders.)

At this point the APA decided to go on the offensive. In a “Commentary,” “The Conceptual Development of DSM-V,” in the American Journal of Psychiatry in June 2009, four prominent officials and advocates of the DSM-V process laid out a lengthy essay that included the history of the DSMs, a presentation of psychiatric advances in recent years, and the authors’ plans for DSM-V. Prominent were their statements that they were poised to carry out field trials and had decided that “one, if not the major difference between DSM-IV and DSM-V will be the more prominent use of dimensional [not purely categorical] measures in DSM-V”. The authors of the Commentary, also traced specifically the intellectual origins of DSM-III and of the Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) that had preceded it, both of which had been under the leadership of Spitzer. But the Commentary pointedly avoided mentioning his name.

At just this juncture, Allen Frances dramatically entered the fray. He had stuck his toe in once, eight months previously, in a short editorial in the American Journal of Psychiatry, co-authored with someone else who also had already worked on the DSMs. They told of a “mistake” that had been made in DSM-IV that had brought about “serious problems” in the diagnosing of sexual offenders, and they advised the DSM-V Task Force to beware the “unintended consequences of small changes.” But now, in June 2009, Frances echoed the same theme in a lengthy and far-reaching article in the Psychiatric Times, warning, among numerous other caveats, that some of the proposed revisions for DSM-V might well produce more harm than good. DSM-V, he predicted, was on the road to a “wholesale imperial medicalization of normality that will trivialize mental disorder and lead to a deluge of unneeded medication treatments—a bonanza for the pharmaceutical industry . . . .” As things stood now, the whole revision process was “badly off track” and could not meet its announced publication date of May 2012. Not only did Frances echo many of Spitzer’s challenges, but he concluded by calling on the Board of Trustees of the APA to establish an external review committee to monitor the work on DSM-V.

The response of the APA, also in the Psychiatric Times, was swift. Under the lead authorship of its president, it declared that Frances’ “factual errors and assumptions about the development of DSM-V . . . cannot go unchallenged.” It took on Spitzer as well. It repeated its position that “the process for developing DSM-V has been the most open and inclusive ever.” It excoriated Frances for ad hominem attacks and defended the goals of DSM-V as against those of DSM-IV, which he had edited. That revision, it said, had sought merely to mark time. The APA hit out against the categorical diagnoses of DSM-III, fine for their time, but now “holding us back.” Finally, it accused Spitzer and Frances of being motivated in their attacks on DSM-V by monetary considerations. Both men, it was pointed out, stood to lose their royalty payments once DSM-V appeared and publications related to DSM-III and IV were no longer sold.

Spitzer answered the next day, on the “ugly turn” the debate had taken, with the APA’s claiming that his and Frances’ motivations in critiquing DSM-V were financial. He seconded Frances’ assertion that a May 2012 publication date was chimerical. Field tests were slated to start immediately, he pointed out, but no drafts of DSM-V had been made available. The public should be informed immediately “the specifics of where DSM-V is going.”

Within a few days—we’re now in early July 2009– Spitzer and Frances followed up with a bold open letter to the APA Board of Trustees. DSM-V was headed for “disastrous unintended consequences,” they charged. “The rigid fortress mentality” of the DSM-V leadership meant it had “lost contact with the field . . . by sealing itself off from advice and criticism.” They warned that if DSM-V stayed on its path, increasing public controversy would arise, and the APA’s publishing monopoly of the DSM would come under scrutiny. The Board of Trustees should “save DSM-V from itself before it is too late,” and Spitzer and Frances offered several recommendations that ought to be pursued. (1) “Open the DSM-V process to full transparency. Scrap all the confidentiality agreements. Actively recruit a large circle of advisors.” (2) Before field trials, there had to be input from individuals outside the Work Groups. (3) Appoint an oversight committee that would monitor the DSM-V process. (4) Make the publication date of the manual “flexible.”

A firestorm now erupted. Both defenders and detractors of the APA weighed in. The Psychiatric Times published retorts on almost a daily basis. The bloggers were busy. Daniel Carlat, a psychiatrist at the Tufts Medical School, wrote: “What began as a group of top scientists reviewing the research literature has degenerated into a dispute that puts the Hatfield-McCoy feud to shame.” The wider press began to report on the conflagration. Of note, Christopher Lane, an avowed critic of the DSMs since 2007, accusing the APA of medicalizing normal states such as shyness, had a lengthy column on Slate summarizing the history of the controversy and supporting the attacks of Spitzer and Frances, his former bête noires. The APA defended itself in its own Psychiatric News, disputing Spitzer and Frances, and responded to their accusations “point by point.”

Throughout the summer and fall, Frances published steadily in the Psychiatric Times, plus once in the British Journal of Psychiatry. By December 3, 2009, he was claiming victory in yet another Psychiatric Times article. He cited “anonymous sources” from whom he had learned that within a month or two, the APA would post a draft version of DSM-V and tshen allow an additional month for comments. The same sources, he went on, had informed him that a new timeline was about to be announced that would have field trials following—not before–the period of receiving comments and would push back the date of publication of DSM-V one year to May 2013. Frances pointed out that only “external pressure” had brought about these “improvements” which also included the APA’s Board of Trustees appointing an oversight committee to monitor the work on DSM-V. He concluded by urging the “research community” as well to apply pressure for continued caution by the DSM leadership. The APA, he suggested somewhat ominously, would be “exquisitely sensitive” to researchers’ pressure since it needed their support if it wished to keep the “franchise” to continue to publish the DSMs.

The APA showed that it was ready to bow to the inevitable by giving Frances space in its American Journal of Psychiatry to publish a short editorial, “The Limitations of Field Trials: A Lesson from DSM-IV.” And on December 10, the APA issued a press release announcing that they were extending the date of publication of DSM-5 a year, until May 2013. (This is the point at which the APA seems to have shifted from calling the new manual “DSM-V” to “DSM-5,” as if to show that the revision signified a departure from the “old” DSM-III and IV.) To cover over an embarrassing situation, the President of the APA bravely declared this lengthening of the timeline would allow “more time for public review, field trials, and revisions.” The press release gave as an additional reason for the time extension that it would allow the APA to better cooperate with WHO as it worked to release its next revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) due out in 2014.

Two months later, on February 10, 2010, the APA posted the DSM-5 draft online (www.dsm5.org) and declared it would accept public comments until April 20. The day after the draft appeared, Frances and Spitzer (although in later postings Spitzer’s name no longer appeared) joined forces to publish in the Psychiatric Times “Opening Pandora’s Box: The 19 Worst Suggestions for DSM5.” (http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/print/article/10168/1522341?printable=true) Obviously, they had not composed this lengthy broadside on “Problematic New Diagnoses” overnight. And not surprisingly, their article did not end just with their critique but with five new suggestions to the APA’s Oversight Committee advocating: extending the time allowed for public review; careful editing “of each word; ”public review of the field trial methods; establishing three Oversight subcommittees to monitor “forensic review, risk benefit analysis, and field trials;” and posting the plans for cooperation with WHO.

The public revelation of the DSM-5 draft triggered immediate reaction from the print and Internet media as well as from the blogosphere reporting on the history of the two-year controversy that had surrounded the revision of the manual and analyzing the draft itself. Public advocacy groups that had been campaigning for their own wishes for or against the inclusion of certain diagnoses sent out bulletins to their members. Well known commentators like George Will were recruited by major newspapers (in this case the Washington Post) to give their opinions. NPR had a half-hour broadcast, including an interview with David Kupfer and questions and comments from the audience. The online news outlets were numerous, among the major of them: Huffington Post, MedPage Today, abcNews, AP, Psychology Today, PsychologyOnLine, University of Chicago Medical Center (Science Life Blog), YouTube, and PsychCentral. The print publications included The Economist, Science, New Scientist, TIME, the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times and USA TODAY.

*************************

Within three weeks of the APA press release, Frances returned to pressing his cause, sometimes every other day, not only in the Psychiatric Times, but in latimes.com, British Medical Journal, Psychology Today, and the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law. In a five day span, in the middle of March, he warned against DSM-5’s worsening the “epidemic” of ADD (Attention Deficit Disorder), attacked the new diagnoses proposed by the Sexual Disorders Work Group, and argued against the medicalizing of normal grief. He continues to this moment.

A few observations seem in order:

The APA leadership was slow to assess and respond to the strong voices and skillful arguments of Robert Spitzer and Allen Frances and has learned a bitter lesson about the adroit use of the Internet.

The role of the Internet in popularizing and spreading the arguments and charges made by Robert Spitzer and Allen Frances cannot be overstated. Without the Internet, the ease and rapidity of their frequent attacks and challenges would have been impossible. It is worth repeating the trite observation that the Internet is the printing press of the 21st century, well adapted to fomenting upheavals.

I have not documented the innumerable blogs the many lay advocacy groups sent to their members nor the fervid online discussions of controversial matters by the public at large. Examples of the latter would be the proposed autism spectrum under which Asperger’s Syndrome would be subsumed or the wished for inclusion in DSM-5, by scores of divorced fathers, of the diagnosis of Parental Alienation Syndrome. The attempt by the public to weigh in on scientific decisions is here to stay. The only question remaining is how scientific and medical groups are going to react to ever-louder lay voices which will only increase as they are facilitated by Facebook and Twitter or other social and professional networking sites.

The Psychiatric Times, founded 18 years after the APA’s Psychiatric News, has profited greatly as a result of its being the main vehicle by which the two former DSM editors circulated their views. This print and online news magazine has perhaps catapulted itself into being the leading news source in American psychiatry.

It is too soon for accurate and coherent public discussion of internal events in the APA that brought about its seeming capitulation. This is, however, a story impatiently awaited by the thousands of readers who followed its unfolding. A knowledgeable and full exploration of Allen Frances’s ongoing intense critiques of the making of DSM-5 may take longer.

It has been speculated by some that the much-discussed Confidentiality Agreement was designed especially to prevent Task Force and Work Group members from publish anything about DSM-5 unless it was through APPI—the APA’s publishing arm which provides the APA with millions of dollars of additional revenue.

The greatest curiosity attaches itself to events yet to unfold as the revision process of DSM-5 goes on. There are many who hope to hear more from the official leadership of the Manual and the APA itself than has been the case up to now. However, Allen Frances’ contribution will not diminish if he has anything to say about it.

To read the other posts on the DSM-V, click here.

On behalf of Psychiatric Times, I would like to thank Prof. Decker for discussing this important issue, and for noting the critical role Psychiatric Times has played in bringing the DSM-5 controversy before the psychiatric profession, the general public, and others in academe. We have been privileged to act as the de facto “paper of record” in this debate, and we hope to continue that role in the months ahead.

Sincerely,

Ronald Pies MD

Editor in Chief

Psychiatric Times

Really interesting post. Truely!

This is what you get when you sit around a connerefce table and vote on whether a disease entity exists! Can you imagine oncologists voting on whether cancer exists? Can you imagine doing away with diabetes by a committee vote of physicians? Despite its efforts to rid itself of psychology, sociology, anthropology and philosophy, psychiatry cannot just wish away the complexity of human adaptation and substitute dumbed down neurobiological reductionism for critical and holistic thinking about people and their problems.

I could not agree more!

No mention of the 2008 12,000 signatures petition (10,500 electronic, 1500 paper) calling for the appointment of Kenneth Zucker to be revoked. Unprecedented.

As a PhD candidate in Psychology who spent the bulk of my educational years under the drama of the DSM-V/5 developments, may I say the drama that unfolded illuminated the best and worst our field has to offer. To look objectively at the issue is to recognize that human beings are flawed, biased and subject to confirmation bias no matter who they are. Psychiatrists are not immune to this reality. It has been a great teacher, and has also made me embarrassed at the one key factor in the entire drama which has been overlooked: The client/patient. Culture, age and socioeconomic conditions seem to be lost to the DSM-5. How does one attribute continued isolation in the geriatric years to a personality disorder if the client/patient has limited mobility? If the client is of a collectivist culture, isolation may not be isolation at all, but merely a learned behavior. How was this overlooked?

As Robert Frost once wrote, “We dance around in a ring and suppose, but the secret sits in the middle and knows.” Perhaps humility is in order. To admit the secret of how experience influences human personality and behavior is the greatest mystery of mankind might be a genesis for common ground. The greatest book of all times, the Bible, hasn’t even cracked that code, though it has come close to addressing it better than the DSMs.

Arrogance in our view of ourselves as clinicians seems the world’s greatest hope. Thus far, I’m not seeing it, but who am I? Just a lowly PhD candidate who will be using this blog as a source for an article. Thank you for writing it! It did encapsulate all the information in a nice, tidy order!