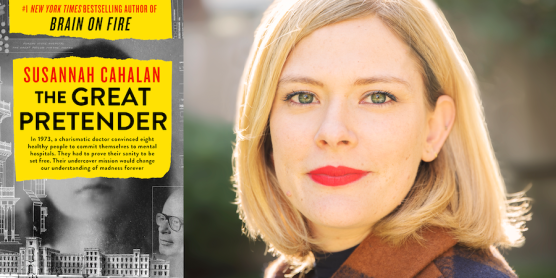

We are delighted to have journalist and author Susannah Cahalan take part in our “How I Became a Historian of Psychiatry” series. In her bestselling 2012 memoir, Brain on Fire, Cahalan recounted her descent into madness—the harrowing experience that brought her, as a young woman in her 20s, into a whirlwind of psychiatric hospitalization, mislabelling, and medical mystery. First diagnosed with bipolar disorder, then schizophrenia, she was eventually found to have a rare form of autoimmune encephalitis. This experience—and her recovery—made her interrogate the very real issues surrounding diagnostic uncertainty.

In her new book The Great Pretender, Cahalan tackles similar topics but with a different approach. The subject this time is no longer the author but psychologist David Rosenhan, whose now classic 1973 exposé of the psychiatric institutionalization system, “On Being Sane in Insane Places,” remains one of the most-cited articles in psychiatric literature. Rosenhan’s study of pseudopatients admitted to various psychiatric hospitals across the US uncovered some unsettling truths about institutionalization; in turn, through careful detective work, Cahalan finds gaps in Rosenhan’s story. This ground-breaking research, she concludes, is the work of an “unreliable narrator.” Yet by exposing psychiatry’s limitations, Rosenhan touched upon an important—and still timely—question: How do we draw the line between sanity and insanity, and what do we do about it?

The Great Pretender is a fascinating study in archival reconstruction; a meditation on the ethics of scientific research; and an elegant exploration of antipsychiatry and its afterlives.

***

Interviewed by Alexandra Bacopoulos-Viau

Alexandra Bacopoulos-Viau (ABV): One of the things I admire about The Great Pretender is how seamlessly you move between your role as an insider—a former psychiatric patient—and an outsider—someone who’s writing about the field as a journalist-turned-historian. How was the writing process different when writing about yourself and when writing about Rosenhan?

Susannah Cahalan (SC): At first, my knee-jerk reaction is to say: Oh, it was totally different. But then when I think about it—Brain on Fire, in many ways, even though it was about myself, I don’t remember such a good chunk of that time. So I really had to investigate that time and use the skills of a journalist—and a little bit of a historian of a lost time… my own lost time!

ABV: You were, in that first book, your own unreliable narrator.

SC: Exactly! So in many ways, it wasn’t different with The Great Pretender, but what was different were the implications of getting things wrong and trying to remain fair, and knowing that there was a huge history out there already. I always loved Edward Shorter’s A History of Psychiatry, and when I was doing this, someone whom I interviewed told me, “You’re doing a history of psychiatry, there are many histories.” And I think, knowing the amount of work that’s out there felt very challenging and, honestly, very frightening to take on.

So it felt higher stakes in some ways, it felt kind of perilous. Again, to quote Shorter—the history of psychiatry is a minefield. I love that line. I felt that way often; I tried to be as balanced as possible while also presenting my own bias. I came at this history from a very biased perspective and I wanted to be very honest about that perspective. And that perspective touches on what history I chose to include and what I chose not to. But when it’s your story, if you get it wrong, it would be really bad for—you know, Thanksgiving dinner. But when you’re talking about this other story—in this case, another person’s life, Rosenhan in particular—I really didn’t want to destroy this guy’s legacy. And I don’t think I did. I hope I was more nuanced. But I didn’t want to go and just kind of disparage him without having solid evidence. So that was also another motivating factor.

Also, in terms of the length of time, it took me one year to write Brain on Fire and it took me six years to write The Great Pretender. So even down to the amount of time, you can tell it was a real challenge.

ABV: How did this historical work differ from your work as a journalist? What did you do differently?

SC: Oh, my gosh! This was an education for me on so many levels. It actually has changed the way I would think about approaching journalism from now on. One of the surprises of this was academic fraud and how prevalent it is. This is not just in 1970, this is happening right now. And I started to think about all the articles that I’ve written for tabloids, you know, like a quick turnaround about some scientific paper, and I just took it at face value. I always knew this on some level—I’ve written about academic fraud in the past, it interested me. But this reminded me how important it is to remain skeptical, and how important it is to have really trustworthy sources. Luckily, over the course of six years [for The Great Pretender], I had amassed quite an arsenal of people I could go to and say, Does this make sense? Does that make sense? Just having that large support system of scholars and academics and people in the field was of huge difference than when you’re just writing about something for a quick turnaround. It was a totally different approach. So it’s very much changed the way I view my own journalism now—and the way I view academia.

ABV: Rosenhan’s 1973 paper [“On Being Sane in Insane Places”], you argue in the book, “as exaggerated and even dishonest as it was, touched on truth as it danced around it.” How has the response to this book—and its relation to the truth—been different amongst psychiatrists, historians and the wider public?

SC: That’s a really interesting question. What’s been fascinating to me—and I have to tell you, I was very nervous about how it was going to be perceived by various factions. What I’ve noticed is that the book is a bit of a Rorschach test, so you kind of see in it what you want to see. As you know, medicine is political—I mean, everything is political, right? People are in camps. And I’ve noticed, on various sides you have people who don’t agree about anything. I’ve gotten positive feedback from both sides, from multiple sides. And it’s been really amazing.

The general public, I think in a lot of ways they approach it from the way that I maybe did, as a kind of education. I think there’s a lot of “Oh, I didn’t know that this happened, oh, I didn’t know about Rosemary Kennedy.” I think there were a lot of surprises, and the mystery of who was this Rosenhan character is intriguing for the lay public.

ABV: You mention that “medicine is political.” And you do certainly delve into certain political topics related to contemporary psychiatry in a way that I find at once passionate and sensitive—e.g., deinstitutionalisation, which, as you note, many have called transinstitutionalisation. In your opinion, can one write a history of psychiatry without thinking about these kinds of implications? Is this what you mean at the beginning of the book when you write “You have to look backward to see the future”?

SC: In terms of the way I view it, again coming from this personal place, I see psychiatry every day around me. When I’m walking to work or walking around my neighbourhood and I see someone who’s very clearly floridly psychotic and living on the street, I see this as part of a history. I can’t extricate that from the general history—and that’s my own personal experience bleeding into my understanding of that history. So, I don’t think you can separate it, not in my view. Someone else probably would have a different view. But I think, especially the deinstitutionalisation which we talked about, and the aftereffects, what we’re living with now—rampant homelessness, a high percentage of people who are seriously mentally ill and their presence in our jail systems—it’s part of life. The general public, since they have a lot of interaction with more negative outcomes of this history, especially in dealing with psychotic people living on the streets, I think this had to inform how I wrote the book and what I chose to focus my lens on in the retelling of “a” history.

ABV: Speaking of politics, I quite enjoyed that footnote about Bernie Sanders having been a Reichian.

SC: When I saw it, I said I have to get this in there! That’s the thing about this history. I mean you’re a historian, you know. I really fell hard for those rabbit holes—you chase something down and all of a sudden, this whole world opens up to you. For example, there’s this one chapter I wrote about Essalen and its connection to Agnews State Hospital, where Bill Underwood stayed. And it was one of those things where you open these doors and ten other doors open behind it. So I wonder how common that is for all of you who study history and who write in these areas. It felt very exciting to be in the archives and to be pursuing some of these histories that may be not well known. I found it so exciting, I really did—it was a joy, really, those parts, I really loved the history. Writing is really hard, but the history was thrilling.

ABV: And then the gaps in the archives—I liked what you did with those gaps, how you explicitly took us through your research process by trying to make sense of the missing dots. Gaps aren’t always addressed in classic historical accounts.

SC: I agree. In a way, what was really depressing for me was not only how badly we treated so many people in the past who were seen as mentally ill, but we actually made them disappear. So many of these hospitals don’t exist now, or they get rid of their medical records. I heard that Saint Elizabeth’s, for example, only keeps the records of patients if their hospitalization ended in a zero or a five—I mean, I’m making up the numbers, but it was something like that—say if you’re hospitalized in 1963, your hospitalization records are gone. And I just think that what we choose to keep and what we choose to discard shows where our interests are and what we find important. And I think even now, we’re still dealing with this idea that mental illness is somehow less important or something. It’s disturbing.

There were other stories that I heard, about cemeteries where people who had been institutionalized died in the hospital, and then they were buried on the grounds, and there were stories of people not knowing that they were cemeteries, clearing the fields of these “piles of rocks,” and only after realizing after the fact that the those rocks were headstones.

So, you know, part of this reckoning with that is reckoning with our view of people who are mentally ill, and that idea that these illnesses—and the people who have them—are less significant.

ABV: On the topic of lost voices, when you read all those history of psychiatry books as part of your research, did you find yourself thinking that something was missing, that there was something you’d like to read more of in those accounts?

SC: That’s a really good question. I mean, I think the first-person narrative is always so powerful, right? And I’ve read a few of them, and some of them are better than others. And sometimes you have an issue where the person who maybe could have written that perfect history might not be capable of doing it—or wasn’t taken seriously enough to be able to do it. There are a few modern examples, though. Did you read Esmé Wang’s book, The Collected Schizophrenias?

ABV: No, I haven’t.

SC: I highly recommend that book; it’s extraordinary. But yeah, I think a lot of the first-person perspective, what it was really like to live on the floors, on the wards—I mean, you can get that here and there, and I have quite a few first-person books that I’ve encountered, some better than others, like I said. But I think that if you really want to get a sense of what it was like to be in an institution back during whatever era, you have to really read the first-person narratives—and so many of them either haven’t survived or never existed in the first place. Have you experienced that as well, in terms of that first-person perspective?

ABV: For sure. And then there are loads of other issues that arise, for instance if you’re looking at earlier times, what does it mean when someone was able to write and publish? How representative is that? It then becomes an issue of selection with certain patient populations, which certainly colours the past—and the present—in very specific ways.

SC: Exactly.

ABV: So there’s a selection bias that happens in itself.

SC: Absolutely! Who was actually capable—and not just capable in terms of the writing but also in terms of being too sick to write in a coherent way that would be kept? I think you’re totally right. It’s so true, what even shapes our understanding is what survives. And so many of the narratives have been lost.

ABV: Last question: Are you working on a new history of psychiatry project?

SC: I wanted to ask you, what should I do? (laughs) I don’t know! But really, going through all of my research, and realizing that there were so many rabbit holes, and things that I got obsessed with briefly or even for a longer time, which didn’t make their way into the book, got me thinking: What do I do with all this? I don’t know that there’s anything to be done with this. I don’t think that I’m done with these topics, I just don’t know what the next step will be. Please help me!

ABV: Well, let’s certainly continue these discussions! But whatever form your next project takes, I speak on behalf of many of us at H-Madness when I say we do hope you’ll keep up with this fascinating work.

Many thanks to Susannah Cahalan for sharing her story!

Excellent book!